Where the Cultural & Clinical Meet: Integrating Distress & Spirituality

Ingo Lambrecht is a New Zealand-based clinical psychologist  and consultant with over 20 years of experience. His book, Sangoma Trance States: Exploring Indigenous Consciousness Disciplines in South Africa, skillfully interweaves personal experience with scholarly research to map the specific non-ordinary states of traditional South African healers. He has clinical experience in a variety of settings in South Africa and New Zealand. Using a collaborative, integrative approach, he works with a diverse group of people of all ages, who present with a wide range of issues and difficulties. He is currently a consultant and project leader for the integration of various Māori mental health services in New Zealand. With a long history of working with people who have cultural and/or spiritual concerns, his special interest lies with the complex clinical work related to the cultural-clinical interface for indigenous people. For more of Ingo’s perspectives on non-ordinary states and psychological distress, please see his highly informative presentation on Shamanic Spiritual Emergencies.

and consultant with over 20 years of experience. His book, Sangoma Trance States: Exploring Indigenous Consciousness Disciplines in South Africa, skillfully interweaves personal experience with scholarly research to map the specific non-ordinary states of traditional South African healers. He has clinical experience in a variety of settings in South Africa and New Zealand. Using a collaborative, integrative approach, he works with a diverse group of people of all ages, who present with a wide range of issues and difficulties. He is currently a consultant and project leader for the integration of various Māori mental health services in New Zealand. With a long history of working with people who have cultural and/or spiritual concerns, his special interest lies with the complex clinical work related to the cultural-clinical interface for indigenous people. For more of Ingo’s perspectives on non-ordinary states and psychological distress, please see his highly informative presentation on Shamanic Spiritual Emergencies.

Working as a clinical psychologist in a state-funded mental health center for Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, myself and my colleagues are charged with providing culturally-integrated clinical care to the top three percent of the seriously mentally ill. We serve many patients presenting with severely distressing psychotic states or schizophrenia, and also severe mood disorders such as depressive disorders and bipolar disorders.

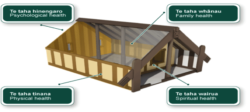

Our model of care is Te Whare Tapa Wha, the House of Wellbeing. This holistic model is based on the sacred communal site of the Marae. Four pillars or aspects of well-being make up the Marae: whanau or family health, hinengaro or mental health, tinana or physical health, and wairua or spiritual health. These four foundational supports hold the protective space of health and well-being for Māori and in fact, it could be argued, for most people. Māori have long built mental health on these four aspects, which they consider necessary to achieve well-being.

Our model of care is Te Whare Tapa Wha, the House of Wellbeing. This holistic model is based on the sacred communal site of the Marae. Four pillars or aspects of well-being make up the Marae: whanau or family health, hinengaro or mental health, tinana or physical health, and wairua or spiritual health. These four foundational supports hold the protective space of health and well-being for Māori and in fact, it could be argued, for most people. Māori have long built mental health on these four aspects, which they consider necessary to achieve well-being.

Distress or extreme states are thus the result of an imbalance of these four aspects, and healing would ideally require the involvement of all four cornerstones. In this way, Māori mental health is clinically sophisticated, avoids reductionism, and also enhances the depth and range of clinical response. It can also address such complexities as the cultural and intergenerational transmission of trauma from colonization.

For example, schizophrenia or psychosis within the Māori model is not merely addressed as a brain disease requiring medications (tinana), nor is it only considered an intrapsychic process treated with any number of psychotherapies (hinengaro). Instead, it also requires understanding the whanau (family therapy, extended family, political systems, the impact of intergenerational trauma, etc.) and the wairua or spiritual realm in the form of voices of the ancestors and other tapu (taboo) issues.

Such a complex formulation then leads to an integrated intervention to help the person heal. The client’s identity is thus reconstituted through this clinical-cultural framework into a new configuration that values subjectivity, relationships, meaning, and spirituality. In Aotearoa (New Zealand), the Māori shaman or tohunga consider mental health difficulties to result from intergenerational afflictions between the living and the tupuna or ancestors. A formulation not so very different from psychoanalytic or attachment theories of mental health.

Furthermore, through personal experience while training as a sangoma in South Africa and doctoral research on shamanic trance states, I have found that the extreme state of hearing voices—usually diagnosed as auditory hallucinations—is a good example of the overlap of mental distress and spirituality. For example, in a clinical setting, a Maori client diagnosed by psychiatrists with severe dissociative disorder and complex PTSD, worked with her severe persecutory voices, but also began to listen to the voices of her ancestors in the room.

Healing means that the ancestors, whether externalized or internalized, serve a positive, engaging, empathic holding function in a newly healing relationship with self and others. Thus, emotional distress and spiritual or exceptional experiences, if acknowledged, at times overlap. In my work, I have come across many clinical parapsychological stories involving lucid dreaming, out-of-body experiences, visions, hearing ancestor voices, telepathy, kundalini syndrome, qigong psychosis, initiation crises, such as ukuthwasa in South Africa, to mention but a few.

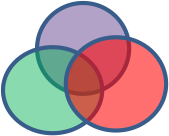

David Lukoff’s model is helpful here, in which three separate spheres depict psychotic states, manic states, and ecstatic or mystical states. He notes that these spheres often overlap in a fluid way, and may share similar extreme states at times. This flexible model allows for the appreciation of how spirituality is involved in mental health, but also how psi events can occur together with distressing states, as is often revealed in clinical parapsychological research.

three separate spheres depict psychotic states, manic states, and ecstatic or mystical states. He notes that these spheres often overlap in a fluid way, and may share similar extreme states at times. This flexible model allows for the appreciation of how spirituality is involved in mental health, but also how psi events can occur together with distressing states, as is often revealed in clinical parapsychological research.

Some spiritual emergencies or crises require careful differential diagnosis, formulation, and treatment. Even in my own shamanic training, this differentiation would occur. Some shamans would discerningly and carefully challenge what is spiritual and what needs to be worked through in a psychological way. Blind and naïve acceptance or denial of psi and spiritual content is not helpful. For example, Western psychiatrists who deny the existence of spiritual emergencies would struggle to find a difference between amafufuyana and ukthwasa—two very distressing psychotic states. They would likely medicate both states similarly. Within a South African sangoma or shamanic tradition, however, one requires medical treatment while the other (ukuthawasa) requires shamanic intervention.

In fact, with a cultural-clinical context, “the paranormal is normal,” according to sociologist Andrew Greeley. Distressing spiritual states are well recognized in many shamanic and Eastern spiritual traditions. They are explained as a difficult process of working through on the path to enlightenment or becoming the wound healer. Within some Western models, this is understood as a part of a psychological individuation (Jung, 1932), a form of transpersonal development (Greenwell, 1990) or a spiritual emergency (Grof & Grof, 1989; Lukoff, 2011).

On the other hand, there can be an equally blind acceptance or simplistic or naïve assimilation of the spiritual in mental health, and that is also concerning for treatment providers and healers of all sorts. Not everyone claiming to be God is enlightened. Ken Wilbur (1983) rightly points out the two major categories of error that are commonly made in attempting to understand a patient’s distress. The first is the reductionist and elevationist error, where all is reduced to a medical issue, for example, or elevated to a spiritual awakening. The second is the “pre-trans fallacy,” in which all is either the result of early developmental processes (pre) or the result of spiritual processes (trans).

Of course how to work with someone to move through such a developmental process while they are in emotionally distressing states that include psi and/or spiritual states, is impossible to elucidate fully here, but I’ve found some of these processes and skills the most useful:

- Normalizing and validating the experience

- Supporting the client in developing self and affect regulation

- Helping the client to integrate and transform their experience

- Holding space for the spiritual aspects of the experience

- Remembering the important socio-political factors that may be influencing this person’s experience

This work at the cross-section of the cultural and the clinical, the spiritual and the psychological, can be highly challenging but it is also deeply gratifying for those of us who value both perspectives.